The Melrose Gallery is pleased to present a solo exhibition by Philiswa Lila titled NOGOLIDE - Sentimental Value in the Tomorrows/ Today section at the Investec Cape Town Art Fair (ICTAF).

-

-

-

A short teaser of the performance

-

NOGOLIDE - Sentimental Value

-

“This body of work and my research practice in general is focused on navigating the role of memory in family photo albums. I am particularly interested in memory histories and personal identities by focusing on story telling methods associated with remembering that conveys a connection with sentiment or relational experiences.

I use my family photo album as a visual material that aids the performance of past memories in the present. The artworks are my reflection on the photo album as an emotional register, occupying the spaces between people and people, people and things and people and places.

Therefore, I evoke personal experiences that materialise in the sensory and the imagination of objects and narratives that generate connections with sentimental value or what is considered sentimental. I use painting, beading, performance and other artforms to creatively reflect on the narratives attending to recollection, interpreting the symbolic relational properties and narratives of remembrance and of piecing together memories”.

The Tomorrows/ Today Section at ICTAF is to be curated by Nkule Mabaso (Curator at Michaelis Galleries, Cape Town) and Luigi Fassi (Artistic Director of MAN Contemporary Art Museum in Nuoro, Italy).

-

Philiswa LilaOnobuhle – beauty contest, 2022Oil on duck cotton canvas170 x 170 cmSold

Philiswa LilaOnobuhle – beauty contest, 2022Oil on duck cotton canvas170 x 170 cmSold -

NOGOLIDE

Thabo JijanaWe invite ourselves into the images of others or wait to be let in, ready for a handshake or to quarrel, toyitoying in feet first, widening the frame, scratching at the canvas, more sun please, a rosy question, fading laughter, affinity. I am the model and the audience, looked at and the one doing the looking. I inherit the many afterlives of my own skin. I am this gaze that returns prestige to a woman whose true medium is her muscular name.

The eye is a mute camera, the heart’s advocate and confidant; the hands that dig the gold also tremble to fix the camera in my direction, the paint brush combing my eyebrows:

It’s a landscape yelling at you.

It’s the orange yellow of fire. It’s a man of the cloth with gold teeth. It’s a beloved inquiry.

It’s a talking fly. It’s a shark asking me to lend it my smile. It’s a precious stone.

It’s to offer the present the familiar garments of history.

It’s my doppelganger willing my pictorial past into the now.

It’s a summer for the sculpted self. It’s to prospect the many faces of my archive. It’s to reinhabit myself. It’s strangers I know sometimes without having ever met.

It’s Ntombikhona. It’s Mama Eve. It’s a few epiphanies about what makes village people people. It’s a portrait of the sitter as a multigenerational figure. It’s to substantiate and flavour the pose. It’s the memory of a painting that celebrates a memory. It’s thickening the water with blood, glittering sweat on black foreheads. It’s an heirloom heavy with hearsay and silences. It’s the stories people tell in order to remember themselves in the stories of other people. It’s the theatre of childhood. It’s the magic and intimacy of oil on canvas. It’s an affair between God and metal. It’s the ebb of time itself. It’s the ink of your feelings. It’s a song of female friendship.

It’s Negre’s muse. It’s Mister Apples. It’s Jesus in black trousers. It’s to befriend Dumakude. It’s to rid ourselves of spiritual views. It’s a younger, bewitching me.

It's a birthday salad to tame.

It’s funeral salads to reference.

It’s the zama zama spear. It’s V Mash’s wig. It’s Mr Goldfingers.

It’s the find of Mapungubwe.

It is the holy city and the altar.

It is Precious, it is the land; it is Nogolide.

© Thabo Jijana, 2022

-

Philiswa LilaMy Schools Days – half card , 2021Oil on canvas170 x 170 cmSold

Philiswa LilaMy Schools Days – half card , 2021Oil on canvas170 x 170 cmSold -

I am particularly interested in memory histories and personal identities by focusing on story telling methods associated with remembering that conveys a connection with sentiment or relational experiences. I use my family photo album as a visual material that aids the performance of past memories in the present. - Philiswa Lila

-

Philiswa LilaNontutuzelo, 2021Oil on duck cotton canvas100 x 100 cmReserved

Philiswa LilaNontutuzelo, 2021Oil on duck cotton canvas100 x 100 cmReserved -

-

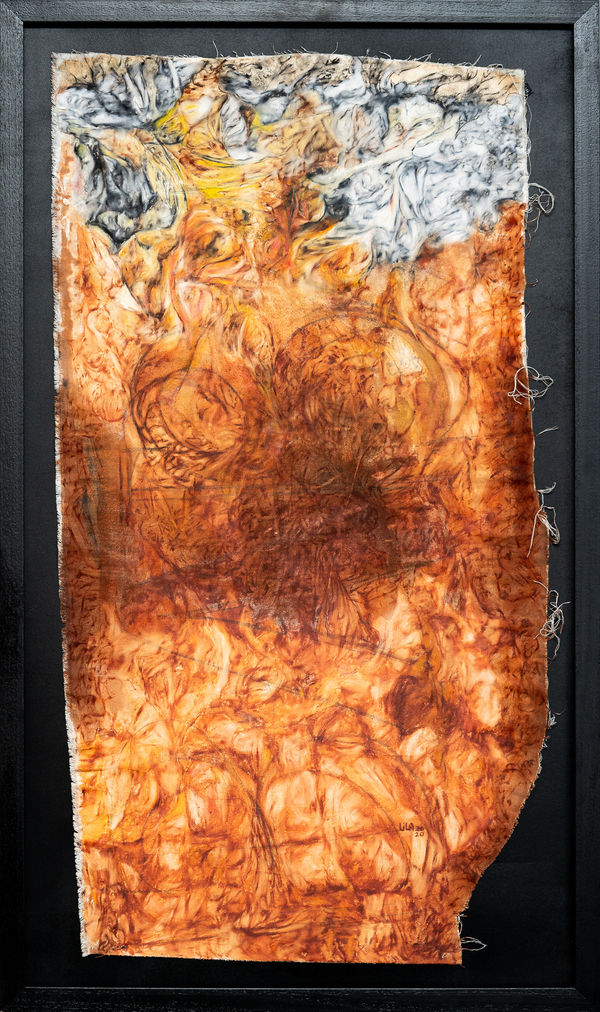

Skin, Bone, Fire: The First Album

-

Through this body of work, Philiswa explores the physical, mental and spiritual spaces held close by her personal experiences. She focuses on the link methods or story methods of remembering. Philiswa is particularly interested in memory histories and personal identities. She is influenced by the nuances of language, meaning and experiences of individualism, especially concerning the physical and emotional senses that are related to humans and animals. Philiswa’s work is multi-disciplinary, including painting, installation, performance and writing. Many of the techniques used in her installations are linked to forms that will fit bodies. Her choice of materials is important to the recording of stories using bodies as archives and traces of personal experiences that connect the past with the present.

-

Absa Art I Philiswa Lila

-

Philiswa Lila’s Skin, Bone, Fire

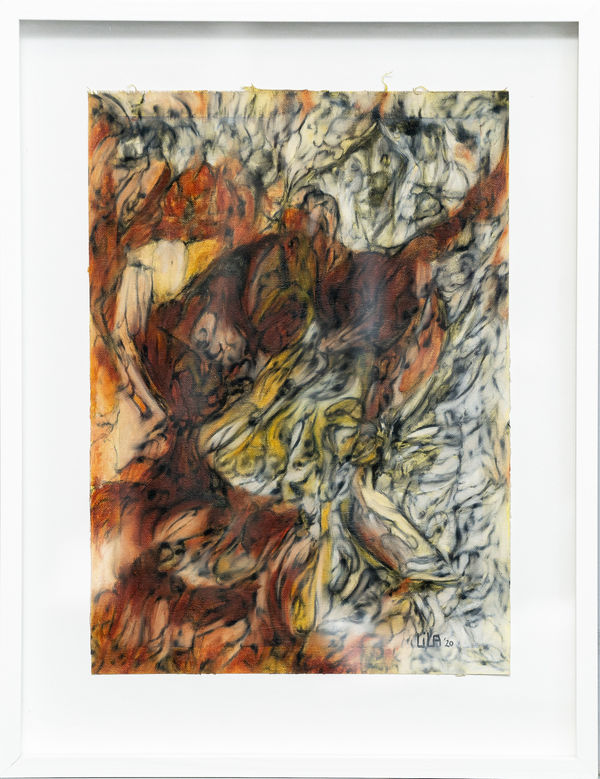

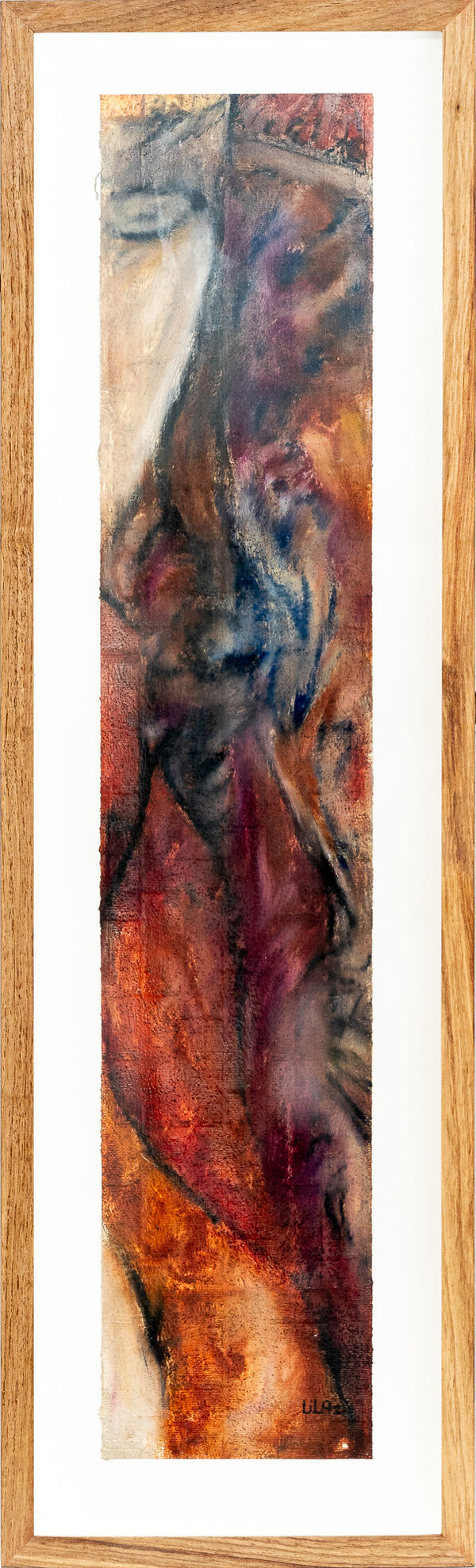

Sharlene KhanPortrait after portrait – Portrait I, II, III, IV, V (2019)– skin begins to look like flames of naples yellow tinged with crimson red and shadows of raw umber and ultramarine, licking the canvas and sending smoke trails of Payne’s grey rising. I think of the Biblical story when Moses stands before a burning bush, and Moses asks God for His name and God says, “I am who I am”

In the beginning, was Adam and Eve, so the story goes.

Or, if you go further back, in the beginning was God, and God created the heavens and the earth.

Perhaps if you want to choose a different beginning, it all started with some gases, atomisation and a big bang.

However it is you chose to enter origination stories – the stories of how we come to think about how we emerged as people – and depending on whether you entered to the left or the right, or walked down the central axis of Philiswa Lila’s exhibition Skin, Bone, Fire: The First Album (2019-2020), you probably could find a visual narrative that is similar to the origination stories above. Entering on the right of the exhibition, is the cover of a photo album with a white couple – the kinds of memorabilia we now only find in parents’ or grandparents’ homes. Adam and Eve. They are the First. The First of those in whose likeness we – people-of-colour here in South Africa – where created. Within the pages of that album our narratives were meant to be similar to that of ‘The Family of Man’[1] to show our family tree, our great heritage, our likeness, our colonial almost-but-not-likeness – that we, too, were human. Thankfully, African lives have always exceeded that by which we were supposed to be bound, and ‘The Black Photo Album’[2] has demonstrated Africans’ sensibilities of aesthetics, familial and wider kinship, an ability to enjoy life despite its hardships, social dexterity as well as being forward gazing. African aesthetics see an interplay between all kinds of modalities and an unembarrassed compositing without giving a preference for any one kind of modality or trend. Looking back at old family albums, once is filled with a nostalgia for the ways in which we bonded and did community, the handiwork of our mothers and grandmothers as they arranged their families and aspirations on these pages.

If you entered the exhibition on the left, you might have encountered uThixo umdali as they were creating: you might have found the days they were busy, the days they rested, the days that the earth was formless, the days when they were unhappy with what had been made. You may even have encountered the day God made Douglas Hlisela Lila, the grandfather of Philiswa Lila as they both hovered over this granddaughter in the beaded works Mkhulu (2019) and Basanda: Self Portrait (2019). You might find yourself marvelling at the sheer beauty of the dark and light blue that maps out white and black contours which makeup the cool portrait that is Philiswa Lila – surely God, too, did appraise their work and find that it is wonderful in their sight. You would also have encountered the portraits of Philiswa’s aunt and the various women who have raised her, whose matriarchal bodies have moulded and shaped what we have come to know and love as Philiswa Lila, who turns her own handwork to commemorate the soft bodies of these nurturers in the white beadworks Nompelazwe (2019), Simangele (2019) and Nomathembha (2019). Perhaps when you entered down the middle axis, you were struck by what appeared to be a magnificent beaded apron – Mandlakazi (2020) – and proceeded to walk around bewildered by why an exhibition would be filled with titles of abstract paintings, reminiscent of fire and flame, and various beaded objects being called ‘portraits’?

One of the first things I learnt when I studied art in school was that it rarely ever was about what you thought, and that was fine. Everyone brings their own readings to an artwork and great artwork sparks imagination much like Rorschach tests do. The second thing was that in-depth analysis of any artwork revealed as much about the artist as it did the subject matter on display – this was particularly deceptive in cases like still-lives, landscape and portraiture where one assumed that the artist was simply drawing what they saw, as opposed to making a series of structured choices and, as in some cases, that those choices were laying bare aspects of themselves. I remember getting distinctively irritated in university when I was constantly chastised for my subject matter as it was thought by some lecturers that I should be painting Hindu gods and goddesses. It didn’t matter that I was Christian and not Hindu, but this racialised-ethnicised stereotyping made me stay away from such subject matter for more than twenty years. When faced with the same challenge as a black student in university, and told to bring in family pictures to class, Philiswa, instead, brought in pictures of goat skin. Goat skin for her harkened to family rituals and bonds she did not fully understand, that she felt had been secreted away from her since she was a child, and, yet, she was drawn to this materiality as for its subversiveness, refusing to provide her family’s or her own ‘black’ skin for white scrutiny in a university setting. This is a trope many of us are all too familiar with, but Philiswa used the opportunity to gain insight into herself, the rituals that embodied and communicated with the unseen through such sacrifices, viewing this as a process of stripping away by which the truth of a thing is revealed through fire without being consumed.

Portrait after portrait – Portrait I, II, III, IV, V (2019)– skin begins to look like flames of naples yellow tinged with crimson red and shadows of raw umber and ultramarine, licking the canvas and sending smoke trails of Payne’s grey rising. I think of the Biblical story when Moses stands before a burning bush, and Moses asks God for His name and God says, “I am who I am”. The bush is not consumed. As I stand before these flames in Lila’s works, I think of the lost and enslaved dancing around the empty idols after they have seen and been fed on the everyday sustenance of miracles. It is not Pharoah that has to let the people go – after all, Egypt is far behind and Pharoah and his might are long dead – but rather, as Roberta Flack says in her song Go Up Moses[3], “my people, let Pharoah go”. I think of celebrations in which people have commemorated marriages, births deaths and festivities. And I think of the image of Ernesto Alfabeto Nhamuave, the Mozamibiquan from the 2008 xenophobic violence, as he was consumed in flames exposing the shamefulness of racial-ethnic hatred that is secreted in our hearts. I think of stories of my own family in which women set themselves alight to escape lives of poverty, the smell of burning skin driving loved ones mad as it lingered in the air, on furniture and deep within noses. Or old Hindu rites of sati in which a widow would throw herself on the pyre of her dead husband, and, in doing so, demonstrated her marital faithfulness, and also conveniently provided a solution for the family inheritance to stay within it. I think of the way in which devotees sometimes show their religiosity by walking over coals of fire without feeling pain, of babies made to inhale the smoke of lighted camphors to clear their lungs, and stories told around fires of who we really are, and shisanyama flames across the world which feed friends and sustains livelihoods.

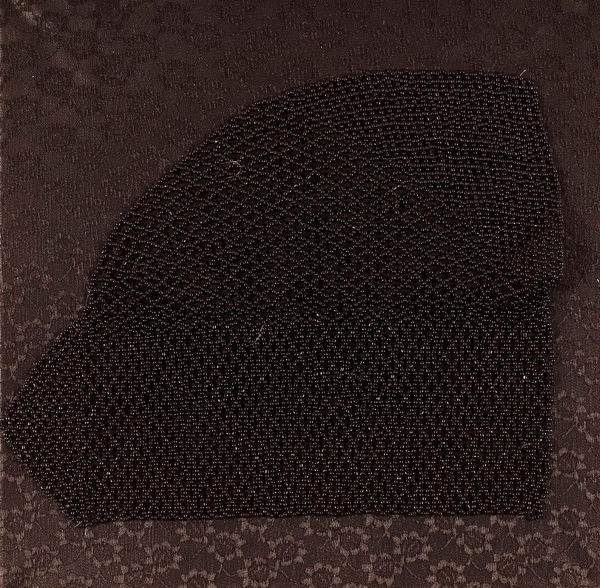

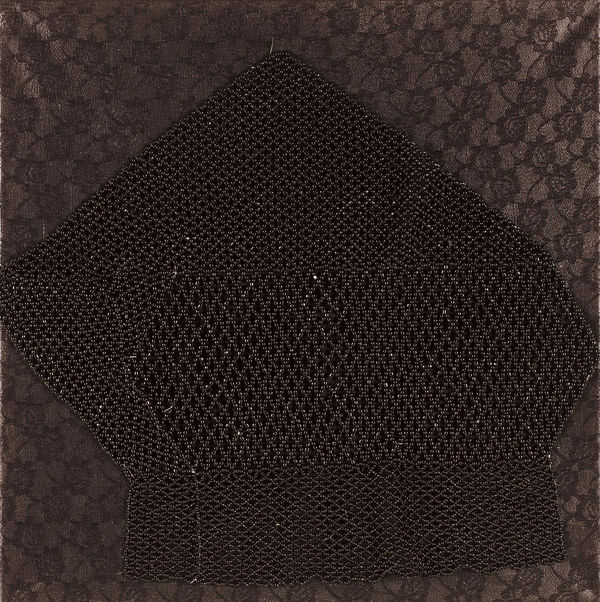

Similarly, Philiswa’s beads are infused with the memories and lives of every interaction she has had. Eastern Cape curator Zodwa Tutani[4] reminds us that beadwork is not simply about colour and pattern and messages sewn to lovers and other viewers, but that as women sit and sew together, as they reminisce and speak about their lives and all that has resided, taxed and enlivened their hearts, all of that lived womanly experience is beaded into work of their hands. Thus, the beadwork, in their proximity to the bodies of their makers, beads act as little dot codes mapping out their existence for all who are willing to sit and view it and allow it to speak to them. We know the strength, intelligence and love of the women and men in Philiswa’s family because of they have been signified so lovingly, so patiently by their maker. Thus, when I look at Lila’s beads and flames, I see the ways in which beads and fire works on skin to reveal the truths of Who-I-am and Who-We-Are, both as individuals and collective societies with long complicated sedimented histories, the truths of which are sometimes lost in time.

Like the truth of pyramids housing golden treasures and great stone cities with canals and delicate hand-crafted gold rhinos smelted in African flames during the Dark Ages right here in southern Africa (long before gold was ‘discovered’ on the East Rand) and 70 000 year old drawings and some of the oldest humanoid remains, all pointing to the portrait that, indeed, what may lie before us as we enter Lila’s exhibition can be read as a coding of the start of human life laid out for us in Xhosa beaded codification. This textured narrative situates African realities which have given birth to humans – the site of the Alpha and the Omega – and not the lies of separatism and subjugated sinful Eves that has we have been told. That when you enter the room of black mourning in which black beaded veils on a black wall are illuminated with a just a hint of light (Zimkitha I, II, II, IV (2019)), it whispers of black fecundity that has birth us all on this great continent. For what Lila creates is an ‘autotopography’[5], in which the objects she creates testify and map out the blueprint of families within families: the axis that that runs from Douglas Hlisela Lila through Philiswa Lila to Mandlakazi (2020), Nompelazwe (2019), Nomathembha (2019) and Simangele (2019) and right down to Sandile (2020) and Kanyisa (2019), it is a blueprint for every single portrait of every human being that walks the face of this great continent and earth. This is indeed what Lila’s Skin and Fire: The First Album reveals - that we are, indeed, flesh of her flesh, and bone of her bone.

[1] A reference to the 1955 exhibition of the same name by Edward Steichen which was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.

[2] A reference to the important work by Santu Mofokeng called The Black Photo Album / Look at Me: 1890–1950.

[3] Roberta Flack, Go Up Moses, 1971, Written by Jesse Jackson, Roberta Flack & Joel Dorn, Atlantic Recording Studios.

[4] Zodwa Tutani and Sharlene Khan (2020), Turbine Art Fair 2020 Special Project: Tactile Visions-Woven, Zodwa Skeyi Tutani, Youtube, 13 August, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYh0o5KGecQ&t=16s

[5] Term from Jennifer González’s Subject to Display: Reframing Race in Contemporary Installation Art, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2008.

-

Philiswa LilaNontutuzelo I,II, III, 2014Beads, String and wood225 x 33 cm(C002337)

-

Philiswa’s beads are infused with the memories and lives of every interaction she has had. Eastern Cape curator Zodwa Tutani4 reminds us that beadwork is not simply about colour and pattern and messages sewn to lovers and other viewers, but that as women sit and sew together, as they reminisce and speak about their lives and all that has resided, taxed and enlivened their hearts, all of that lived womanly experience is beaded into work of their hands.- Prof Sharlene Khan

-

-

Stories of Our Soil and GendV Project

-

Having participated in the residency program GendV Project: Urban Transformation and Gender Violence in India and South Africa hosted by the University of Johannesburg and the University of Cambridge. Through this residency program Lila created artworks that where part of the group exhibition ‘Stories of our Soil’ curated by Ruzy Rusike hosted at The Melrose Gallery in August 2021. The artworks included the beaded sculptural pieces Isilumo (period pains) and Ilokwe yeKresmesi-ndiyamensa mama (a Christmas dress-mama I’m menstruating)

Through what is now an ongoing online exhibiting with My Life, Our Stories Johannesburg, she is observing through this body of work, ideas of pain, love, hurt, desire and the stories that we disclose and those that we choose not to about family life, sexual violence and abuse, teenage experiences, amongst others. Other recent projects include a virtual performative work with the Institute for Creative Arts Online Fellowship (2020) and a photographic series with Home Museum (2020)

-

Philiswa LilaIlokwe yeKresmesi: Ndiyamensa mama, 2021Beads, string, wire hanger, bow104 x 70 cmR 34,000.00

Philiswa LilaIlokwe yeKresmesi: Ndiyamensa mama, 2021Beads, string, wire hanger, bow104 x 70 cmR 34,000.00 -

Philiswa LilaIlokwe yeKresmesi: Ndiyamensa mama, 2021Beads, string, wire hanger, bow104 x 70 cm(C003947)

-

Philiswa LilaMhlaba Uyahlaba , 2020Oil on canvas170 x 300 cmSold

Philiswa LilaMhlaba Uyahlaba , 2020Oil on canvas170 x 300 cmSold -

-

significant meanings

-

What I am mainly trying to convey has to do with storytelling. Daily interactions with objects leave memories in our minds. I recognise that stories and details of stories, those that I choose to remember or choose to forget, are part and parcel of the process of telling through creative reflection and recollection. In the process of creating the artworks, I also investigate how objects influence people’s remembering and usage. - Philiswa Lila

-

More on Lila

-

-

News

-

Artists opt for virtual exhibitions

26 Apr 2020Visual artists are swapping gallery exhibitions and showcases for virtual ones, as most of the world remains on lockdown. Visual artists are swapping gallery exhibitions and showcases for virtual ones,... -

CHRIS THURMAN: A Swirl Of Bodies In The Age Of Digital Reproduction

Philiswa Lila 21 Feb 2020When it comes to Philiswa Lila’s exhibition Skin, Bone, Fire, a virtual experience is not quite the same as being in a room with the art Long-term readers of this... -

Absa Art Gallery

Philiswa Lila 21 Feb 2020Watch Philiswa Lila give us her take on the future of visual arts and a new generation of trail-blazing African artists. Discover what her art is made of and visit... -

Navigating personal memories in my family photo album

By Philiswa Lila 6 Dec 2021A photo album is an intimate object that plays an important role in the construction and image of family life. An album presents a visual narrative that can influence how...

-

-

My artworks, curating and research are not separate, or I am not trying to create a separation between them. I don’t treat the precious mentioned as individual positions either. When I am curating for an exhibition I am creating an artwork, and I treat research the same way. They all speak to each other because I am then able to consider things like exhibition space and the environments where my work is shown, including creative practice writing and publishing, which is something I am interested in developing. - Philiswa Lila